The

Baltic harbour porpoise

The harbour porpoise is the only whale resident in the Baltic Sea, but it is critically endangered.

Photo credit: Buiten-Beeld / Alamy Stock Photo

the Baltic Sea

animals left

Classified as

critically endangered

The harbour porpoise is the only whale resident in the Baltic Sea.

It has been present here since the Baltic Sea formed some 10 000 years ago, but today there is only a small remnant of the historical population left. With only a few hundred animals , the Baltic Proper harbour porpoise is critically endangered, and urgent measures are needed to save the population.

Unfortunately, there are

many threats to harbour porpoises:

- They can get caught and drown in fishing nets, and bycatch is one of the primary reasons there are so few porpoises left in the Baltic Sea today.

- Loud underwater noise from explosions and offshore constructions of for example windfarms can make a porpoise deaf, which will eventually lead to its death because a porpoise depends on its echolocation to find food.

- Noise from heavy shipping traffic and fast leisure boats can cause disturbance, altering important behaviours such as feeding, mating or nursing of calves.

- Environmental contaminants and pollutants such as PCB can cause decreased fertility in harbour porpoise females, as well as increased susceptibility to disease and parasites.

- Overfishing and ecosystem changes can make it more difficult for harbour porpoises to find enough prey.

Photo credit: Sven Koschinski - Fjord and Belt, Kerteminde/DK

Photo credit: Anthony Pierce / Alamy Stock Photo

To ensure the survival and recovery of the critically endangered Baltic Proper harbour porpoise, Baltic countries should :

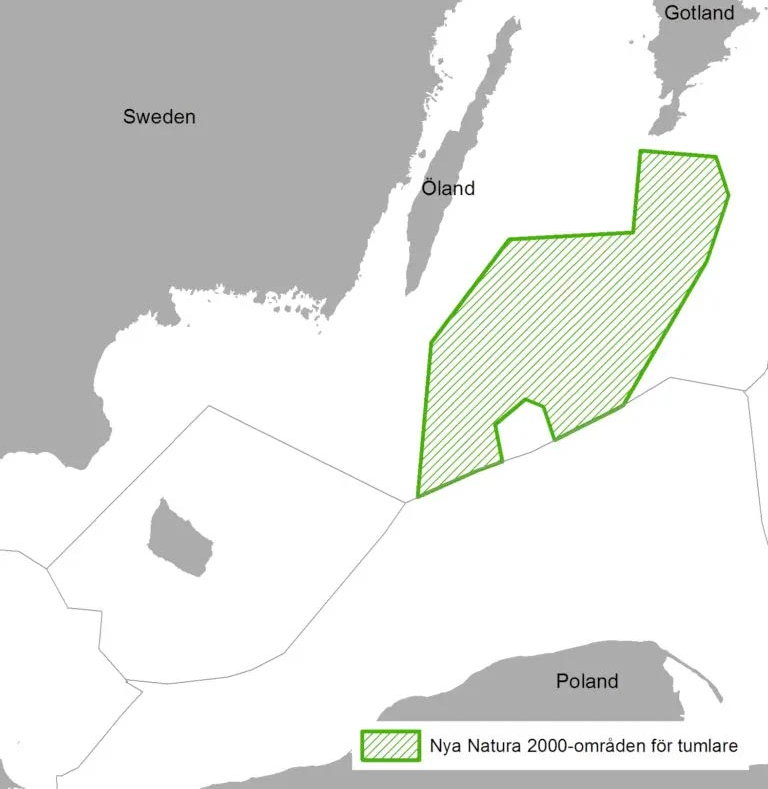

- Take effective conservation measures in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) for harbour porpoises. This includes seasonal or full-year closures of high-risk fisheries, re-routing of shipping lanes and strict limitations of offshore constructions.

- Follow the ICES scientific advice on how to minimize bycatch of harbour porpoises in the Baltic Sea, including the use of pingers in static net fisheries in the entire population range.

- Conduct at-sea tests and assess the effects of pingers on military underwater activities and the possibilities for co-existence. If pingers are shown to be a security risk, alternative conservation measures need to be implemented.

- Increase efforts to develop and implement alternative fishing gear that does not cause harbour porpoise bycatch.

- Ensure that a second survey, SAMBAH II, is carried out of the population abundance and distribution.

In December 2020, BALTFISH sent this

Joint Recommendation to the European Commission, to prevent bycatch of Baltic Proper harbour porpoise in the Baltic Sea fisheries.

In September 2021,

this Joint Recommendation was also submitted to the European Commission. Both Joint recommendations includes measures only within Natura 2000 areas. The JRs have been transposed into a

delegated act which will be implemented during spring 2022.

The Baltic proper harbour porpoise

is critically endangered.

Your help

is vital to protect the only whale in the Baltic Sea!

Between 12 August and 1 October 2020 we did a quiz in collaboration with Humane Society International to find out how much people know about animals in general and, in particular, how well-known the harbour porpoise is.

We did this because some populations of harbour porpoises are endangered and urgently need our help and people, in general, want to protect what they know. So, this was a test of public knowledge and also an exercise in raising their profile.

All about the Baltic harbour porpoise

What can you do?

Your voice is important in this work. We need your help to convince the politicians that protecting the Baltic Proper harbour porpoise is important, so that they make the right decisions on harbour porpoise conservation.

Please show your support by signing our

petition, and share it with your family and friends!

You can also

donate and show your support through our dedicated

Facebook and

Instagram pages, and tag your photo of the sea with #SaveTheBalticPorpoise or #RäddaTumlaren.

Also, if you spot a harbour porpoise at sea, please report it to your national reporting hub.

This photo shows a young harbour porpoise male found on a beach in Poland in October 2016.

He has clear marks of nets around his mouth, showing that he was caught and drowned in a fishing net before drifting ashore on one of the long sandy beaches on the Polish coast.

Don't forget to report a harbour porpoise if you see one at sea!

National reporting hub for porpoises

| Country | Organisation | Website | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | Swedish Museum of Natural History Artportalen (Species Observation System) | Sightings and strandings should be reported to https://tumlare.nrm.se Sightings can also be reported to: https://www.artportalen.se/ | |

| Finland | Finnish Ministry of the Environment | https://www.ymparisto.fi/fi-FI/Luonto/Lajit/Lajiensuojelutyo/Yksittaisten_lajien_suojelu/Pyoriaisen_suojelu/Pyoriaishavainnot | |

| Estonia | Nature Observations Database | http://loodus.keskkonnainfo.ee/lva/ | |

| Latvia | Dabas Dati, Nature Protection Agency, Latvian Museum of Natural History | live: www.dabasdati.lv dead: www.daba.gov.lv dead: www.dabasmuzejs.gov.lv | |

| Lithuania | State food and veterinary service, Lithuanian Marine Museum | dead: http://vmvt.lt/ live or dead: http://www.muziejus.lt/ | |

| Russia | Baltic Fund for Nature Kaliningrad zoo | www.bfn.org.ru | bfn@bfn.org.ru |

| Poland | Hel Marine Station, University of Gdansk | www.morswin.pl | hel@ug.edu.pl |

| Germany | German Oceanographic Museum | Info on sightings and strandings reporting: https://www.deutsches-meeresmuseum.de/wissenschaft/sichtungen/sichtung-melden/ | App OstSeeTiere |

| Denmark | Maritime Museum in Esbjerg | Strandings: https://fimus.dk | For sightings there is an app: Marine Tracker by University of Southern Denmark |

Brochure

“The Baltic Sea Harbour Porpoise needs protection”

Briefing

"The 2022 EU delegated act"

"PCB'S AND THEIR LIKELY EFFECTS ON THE BALTIC PROPER HARBOUR PORPOISE"

Baltic Talks about the harbour porpoise

SOCIAL MEDIA PAGES of the

BALTIC SEA HARBOUR PORPOISE

@Raddatumlaren

@raddatumlaren

For more information:

CCB Secretariat:

secretariat (at) ccb.se